someone else’s bookshelf

“Help yourself to any books you want” said the hostess suddenly as an afterthought. Conventional politesse but with a down-to-earth note, like ‘this is your scarf isn’t it, don’t forget to take it with you.’ This was at the end of a long January evening with its bottles of red wine, and dinner improvised out of contributions of nems, quiches, sushi, humous dips, lots of leftover Christmas chocolate, with happy, then squally children playing hide and seek around handsome furniture from China and Iran, countries where the couple had lived for a few years. (‘He’ works for the French car company Peugeot ). I had briefly checked out the well-stocked library corner – a lot more densely packed, neatly organised and new-looking than my own since rather than buy books I use the local mediatheques in Antibes and Valbonne for reading matter in English and French. My bookshelves feature a lot of yellowing sentimental attachments to poetry volumes, over-thumbed teenage copies of Dostoevsky and over annotated authors studied years back . Luckily I’m not starved since the mediatheques are well-stocked, international libraries – the sort that you would only find in capital cities ten years back.

I had definitely absorbed too much good red wine to make a cerebral choice at the time - perhaps the advantage was I’d made an uninhibited one and picked up writers I’d censor for myself when fully sober. I did know I was looking for some writing in between pure factual or prose fiction. I’d considered Yasmina Reza and Chahdortt Djavann’s books before in bookshops and libraries without going as far as taking one home to read. Picking a book off someone else’s bookshelf is different though, like seeing a face you know by sight at a friend’s house so now the acquaintanceship might become personal. Iran is what I had in common with the couple whose house we were in that evening through their having lived there and my partner being Iranian. We hadn’t talked much about that link though and the glaring black hole in any conversation of mine about Iran being that I myself have never visited the country. So the choice of Djavann’s book out of the hundreds of similar paperbacks, was motivated by the underlying curiosity in that place- where-I’ve-never-been. I’m always pulled despite myself, to other people’s readings of Iran.

Reza and Djavann are writers whom I know of from media coverage. They both have fairly high profile personalities in France. Especially Reza for her prolific output in theatre, her interviews on cultural chat shows and most recently from being allowed to follow Sarkozy around and make a book out of his electoral campaign which resulted in the book ‘l’Aube, le Soir ou la Nuit’ ‘Dawn, Evening or Night’ because .’tragedy has no place. Nor any particular time. It (happens)’s dawn, evening or night ‘ – there in this quotation you get the fatal hubris full on. Reza will actually use her genius as a playwright (doesn’t the French dramaturge sound so much more potent) to paint a portrait of a Sarkozy of Shakespearean dimensions an excuse for taking on all the big questions - love, ambition, solitude, the transience of passing time - in that terse poetic style, all barricades up and gruff beating heart anyway underneath it all that is her speciality. Here I have to say that I didn’t know she’d written this book until after I’d read the borrowed novella that evening and then started looking her up on the net for some more precise details. I have to confess that if I’d known she was such a glitterati I’d not have bothered to take that slim novella - the first she wrote - home to read. I have an innate prejudice against artists who hold up a mirror to the powerful of the world. OK Shakespeare wrote his tragedies about tyrants but he was living under a regime similar to Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in terms of human rights and had to save his skin by currying favour on a regular basis.

Thursday, January 29

is it relevant to discuss the mindset a reader brings to a book?

Surely it’s an essential process, more honest - if you believe as I do that books have the power to change you as much as lived experience. The thing is I forget I belive this - that’s the problem. Actually it’s one of the reasons I’m writing this blog on my spare afternoon a week. To remember that books do adjust your reflection on your own life, the quality of how you meet others. As well as to an extent at least, how you develop your relationships with other people. How you formulate yourself.

Chahdortt Djavann is renowned in France for her vehement arguments in favour of a lay culture and against the effect on women of islamic fundamentalism in muslim countries, particularly Iran where she grew up. She is the author of the book “Bas les voiles” that excited a lot of attention in France, officially a lay country since the legal separation of church and state in 1905. And so my initial approach to “Comment peut-on devenir français?” ‘How can one become French?” by Djavann was more than a little clouded. Firstly in my ignorance I didn’t recognise the reference to Montesquieu’s satire on Europeans in ‘les Lettres Persanes’ written in 1721, ‘comment peut-on être persan’ is what the crowds of Parisians mutter when two Persians Rica and Uzbek who’ve been forced to flee their country for political reasons stroll through the Tuileries dressed in their traditional robes. The worst thing about ignorance is that it sends you back to the limits of your own experience for every value judgement and so reading the title brought back my own personal saturation with the emotion around assimilation in France – plus the recurrent media feasting when every now and then high school girls try to wear the ‘islamic headscarf’ to school. I know what it’s like as an immigrant - or apatride - who - on good days - lives out with pleasure (most of) the ways of another language and social culture. Assimilation in a process linked as much to time and nature as the erosive patterns of sea and wind on a coastline. Any implication of a moral imperative therein, smacks of homogenisation, no worse, eugenics - and makes me want to kick something, soon.

Both are writers for whom I felt a similar mélange of interest and tired antipathy. Without reading a single word of their work - it has to be repeated - so I must be talking about myself here. My interest - of course was because of their status as successful writers with a challenging, if not arrogant take on experience. My resistance came from the impression I got that each woman in her own way aligns herself with a certain sort of media appetite for the opinions she puts forward. .

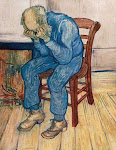

In Reza’s case it was for what I sensed from extracts of her theatre of conventional relationships not exactly the valet hiding in the wardrobe while the mistress of the house seduces the man she doesn’t know is her brother-in –law sort of thing. But nearly. And also that she produces very much a “man’s woman”sort of writing. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Marguerite Duras for instance does the same. Except that Duras is such a figurehead of twentieth century French fiction that before you have time to lose yourself in preconceptions based on her personality/media representation, you experience the writing first. Its music and - to pick up on my last post on Woolf ‘s ideas – and to what happened when I actually read the slim volume of Reza’s entitled in French “Une désolation” (maybe “Desolation” or “ A Grief” in English) - the plunge into writing that feels full of great endurance, openness to life, free of taboo.

The novella is the inner monologue that a successful, retired businessman relegated to the good life in the suburbs of Paris, addresses to an absent hippy son from a former marriage who has ‘done nothing’ with his life except ‘be happy’on some island in the Pacific. I would say that the choice of this framework – the tension and longing in addressing an absent child is only trace of the woman writer. The language is spare - bleached would be a better word (Reza’s reviewers like it too - blanchi in French) to describe the corrosive intelligence behind the curt phrasing and perfect ear for the ping-pong of how the mind moves back and forward presenting and hiding itself in conversation. As I read it I remembered a tv interview with Reza in which she talked at length about her relationship with her father. She got all her juice from him I remember her saying. This understanding of theirs must have given her that insider’s position you can’t fake with the septugenarian’s voice in this book, a whale of an ego, full of angry, ironic grief for the ‘times of destructive passion’ in his own life. He is nolonger in love with his present wife because she has‘chosen happiness’ and ‘effort’ and positivity every morning over her French toast. His days are warmed by his faithful affection for a lifelong friend who sits at a window contemplating the seasonal changes in a tree in the middle of the Parisian traffic. He remembers the sheer lack of choice in his obsessive desire for a married woman and their futureless affair conducted in doorways and hotel rooms. The nearest he gets to grief in the altruistic sense of the word is in mourning the death of a self-made business friend who used all his energy to perfect his flat in the middle of Paris whilst wondering all the time ‘what next’

It’s the tone particular to French – the language and people that I hear everyday, in myself too - a sort of deliberate shrugged -on philosophic mockery. The other side of the coin is a relish of the here and now, la bonne chère they say, a sort of pagan revelry in food and flesh. At its worst a Gallic parochial xenophobia and in its flower as in Reza’s narrator – who knows the world outside France and has lost the love of his son, it provides a keen, very funny reflection on the saccharine compromise of any ‘life-solution’ It’s charismatic in its air of full-on honesty and that is maybe for the first book – for now that I know of her admiration for Sarkozy - not the person but what he stands for - I have a feeling that every book of Reza’s will keep up this unvaried punchy macho attitude to despair. Fun - if you don’t mind spending all your time around strong egos half in love with themselves and their own domestic tragedies. There is that seductive tone of intelligent Woody Allen-esque bafflement too, the one that you like to give yourself up to its making you laugh over and over again at the pitiful misery of life’s illusions. Reza’s protagonist is Jewish too, though cutting off from friends who buy a retirement home in Israel is part of his refusal of ‘the solution’ of his rancid pity for any of those “poor souls” who hope for ‘some accomplishment’, who take up a political stance to explain their own degradation, “optimistes en tutu!”

“Everyday the world shrinks me a little bit more and today the world shrinks in me. That’s the way it goes. Little by little death gains ground. You get used to it. You get used to death. You’re not as upset as all that to join in the rhythm of the universe.”

Reza’s writing is a joy in particular delight for an outsider to the French language like me, with its ear for ironic self-portraiture artfully baked in, as it were to every pause and word. It creates a sense of affection for the character that I don’t feel so much in English. I wonder if that’s because I’m so much inside the language or if it’s that I haven’t lived in an English speaking country for so long.

Chahdortt Djavann is renowned in France for her vehement arguments in favour of a lay culture and against the effect on women of islamic fundamentalism in muslim countries, particularly Iran where she grew up. She is the author of the book “Bas les voiles” that excited a lot of attention in France, officially a lay country since the legal separation of church and state in 1905. And so my initial approach to “Comment peut-on devenir français?” ‘How can one become French?” by Djavann was more than a little clouded. Firstly in my ignorance I didn’t recognise the reference to Montesquieu’s satire on Europeans in ‘les Lettres Persanes’ written in 1721, ‘comment peut-on être persan’ is what the crowds of Parisians mutter when two Persians Rica and Uzbek who’ve been forced to flee their country for political reasons stroll through the Tuileries dressed in their traditional robes. The worst thing about ignorance is that it sends you back to the limits of your own experience for every value judgement and so reading the title brought back my own personal saturation with the emotion around assimilation in France – plus the recurrent media feasting when every now and then high school girls try to wear the ‘islamic headscarf’ to school. I know what it’s like as an immigrant - or apatride - who - on good days - lives out with pleasure (most of) the ways of another language and social culture. Assimilation in a process linked as much to time and nature as the erosive patterns of sea and wind on a coastline. Any implication of a moral imperative therein, smacks of homogenisation, no worse, eugenics - and makes me want to kick something, soon.

Both are writers for whom I felt a similar mélange of interest and tired antipathy. Without reading a single word of their work - it has to be repeated - so I must be talking about myself here. My interest - of course was because of their status as successful writers with a challenging, if not arrogant take on experience. My resistance came from the impression I got that each woman in her own way aligns herself with a certain sort of media appetite for the opinions she puts forward. .

In Reza’s case it was for what I sensed from extracts of her theatre of conventional relationships not exactly the valet hiding in the wardrobe while the mistress of the house seduces the man she doesn’t know is her brother-in –law sort of thing. But nearly. And also that she produces very much a “man’s woman”sort of writing. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Marguerite Duras for instance does the same. Except that Duras is such a figurehead of twentieth century French fiction that before you have time to lose yourself in preconceptions based on her personality/media representation, you experience the writing first. Its music and - to pick up on my last post on Woolf ‘s ideas – and to what happened when I actually read the slim volume of Reza’s entitled in French “Une désolation” (maybe “Desolation” or “ A Grief” in English) - the plunge into writing that feels full of great endurance, openness to life, free of taboo.

The novella is the inner monologue that a successful, retired businessman relegated to the good life in the suburbs of Paris, addresses to an absent hippy son from a former marriage who has ‘done nothing’ with his life except ‘be happy’on some island in the Pacific. I would say that the choice of this framework – the tension and longing in addressing an absent child is only trace of the woman writer. The language is spare - bleached would be a better word (Reza’s reviewers like it too - blanchi in French) to describe the corrosive intelligence behind the curt phrasing and perfect ear for the ping-pong of how the mind moves back and forward presenting and hiding itself in conversation. As I read it I remembered a tv interview with Reza in which she talked at length about her relationship with her father. She got all her juice from him I remember her saying. This understanding of theirs must have given her that insider’s position you can’t fake with the septugenarian’s voice in this book, a whale of an ego, full of angry, ironic grief for the ‘times of destructive passion’ in his own life. He is nolonger in love with his present wife because she has‘chosen happiness’ and ‘effort’ and positivity every morning over her French toast. His days are warmed by his faithful affection for a lifelong friend who sits at a window contemplating the seasonal changes in a tree in the middle of the Parisian traffic. He remembers the sheer lack of choice in his obsessive desire for a married woman and their futureless affair conducted in doorways and hotel rooms. The nearest he gets to grief in the altruistic sense of the word is in mourning the death of a self-made business friend who used all his energy to perfect his flat in the middle of Paris whilst wondering all the time ‘what next’

It’s the tone particular to French – the language and people that I hear everyday, in myself too - a sort of deliberate shrugged -on philosophic mockery. The other side of the coin is a relish of the here and now, la bonne chère they say, a sort of pagan revelry in food and flesh. At its worst a Gallic parochial xenophobia and in its flower as in Reza’s narrator – who knows the world outside France and has lost the love of his son, it provides a keen, very funny reflection on the saccharine compromise of any ‘life-solution’ It’s charismatic in its air of full-on honesty and that is maybe for the first book – for now that I know of her admiration for Sarkozy - not the person but what he stands for - I have a feeling that every book of Reza’s will keep up this unvaried punchy macho attitude to despair. Fun - if you don’t mind spending all your time around strong egos half in love with themselves and their own domestic tragedies. There is that seductive tone of intelligent Woody Allen-esque bafflement too, the one that you like to give yourself up to its making you laugh over and over again at the pitiful misery of life’s illusions. Reza’s protagonist is Jewish too, though cutting off from friends who buy a retirement home in Israel is part of his refusal of ‘the solution’ of his rancid pity for any of those “poor souls” who hope for ‘some accomplishment’, who take up a political stance to explain their own degradation, “optimistes en tutu!”

“Everyday the world shrinks me a little bit more and today the world shrinks in me. That’s the way it goes. Little by little death gains ground. You get used to it. You get used to death. You’re not as upset as all that to join in the rhythm of the universe.”

Reza’s writing is a joy in particular delight for an outsider to the French language like me, with its ear for ironic self-portraiture artfully baked in, as it were to every pause and word. It creates a sense of affection for the character that I don’t feel so much in English. I wonder if that’s because I’m so much inside the language or if it’s that I haven’t lived in an English speaking country for so long.

If you come to the writing first and it's powerful

your pre-reading prejudices and inner babble of opinions and ideas - of which mine include that writing by women from the erotic point of view of men is a cop-out, there’s enough of that around and a woman doing it won’t teach me anything new…melt into irrelevance. That’s the definition of good writing – it shuts you up. You get peace and quiet away from yourself for a while. What a relief!. Suffice it to say that when I finished this book I stocked up on all the prose by Reza I could find at the médiatheque – I’d rather see the theatre than read it. Two similar slim one-voice volumes, an off-beat form, novella-size, between monologue and prose “Schopenhauer’s sled” and “Adam Haberburg”.They’re sitting there on the corner of my desk as I write and I’m looking at them every now and then …and yet – and yet mingled insidiously with that nice sense of anticipation that comes over me when I know I’m going to get to spend time reading a good writer is the niggardly streak of disappointment since I found out about her writing on the presidential campaign. I know I will insist now that she prove her human touch somewhere again. That she shows us something else as well just all that cool, hemmed in verbosity and psychological sleight-of- hand that just tickles you into smirking out loud.

Tuesday, January 13

the reading habit

The only two times in my life I can remember setting a book aside not out of distaste but out of a sheer sense of irrelevance was during in the days following the births of my two daughters. Otherwise ‘the need to read’ - hey, there are worse escape routes – is always there. A mental reaching out for sustenance - the metaphor is telling. Yes, the reading habit is a sort of nourishment akin to food. (So when is reading ‘toxic’? And is this a value judgement amounting to censorship?) I don’t want to sound overly moralising on ‘the value’ of bookishness. I’ve lived with and loved non-readers all my life, just like I’m a non-skier, non-roller-blader, non-chess player and so on. Still it’s good to see this reading trait emerge in my first daughter to whom I have unwittingly handed on so much. She reads indiscriminately, with relish like a foodlover tucking into a meal when she goes to replenish her pile of books from the mediatheque around the corner from where we live. At the minute the she’s finishing ‘The Summer of the Sisterhood’ – what she calls ‘one of those chatty-girly books.’ She’s read all the ‘Twilight’ series, the gothic remake of Romeo and Juliet about a girl in love with a vampire. This Christmas she was caught up in ‘Jane Eyre’ which she liked (she said) because of the atmosphere. Jane is ‘passionate’ she said, (a judgement influenced by French language and culture - where you’re allowed to talk about ‘passion’ with the sort of detachment that would make pre-ados elsewhere cringe). Jane is a rebel too, so she liked that. The shrieking voice from the attic is ‘gothic’ – wild, anarchic and ‘cool’. I promised her the sequel’ to Jane Eyre in one of my favourite books ever – Jean Rhys’ ‘Wide Sargasso Sea’ written from the perspective of the madwoman in the attic. She also read ‘Girl with a Pearl Ear-ring.’ which she liked for its historical setting in Renaissance Amsterdam. She had never realised that Catholics and Protestants could be at war with each other (isn’t such innocence an achievement for the daughter of a woman who grew up in the sectarian atmosphere of northern Ireland a generation back). Nevertheless she thought the servant-girl heroine was “too lucky” – her adolescent heroines are always ugly or unlucky at the start. I don’t think she got the erotic tension between the painter and his model – or maybe she did but couldn’t/wouldn’t put words on it to me. I was a bit surprised that she chose this book from my bookshelf in the first place. It turned out that Vermeer’s painting had turned up in an American soap opera she and her sister watch on You-tube in their week-end ‘screen time’. A character had stolen the Vermeer painting.

virginia woolf

Today at the end of a proliferous second generation of great contemporary women writers it’s difficult to understand how twenty-five years back the sensitivity in Woolf's writing could be such a relief and a release from the official ‘canon’ of English writing that mattered. Doris Lessing complained that Woolf was 'such a Lady she left so much out.' Her poetic side puts people off, as well as her Edwardian class-consciousness – all that talking about the charwoman’s rough red hands and so on. However for me her sensitivity burns through all these social attitudes. She was aware of the price you pay for living outside the ordinary run of happiness. In Mrs Dalloway the portrayal of mental breakdown for the sufferer and those around him is portrayed with great delicacy and detachment too, without the anger or nihilism that leaves such a depressing aftertaste as in the work of Sylvia Plath or Ken Kesey. Woolf might have been in many ways prisoner of her class and time but she understood like that other Edwardian, EM Forster, what it was like to suffer under the perception of the moral majority. She reacted with defensive snobbery to middle class philistines and the working class in her notebooks and diaries and even wrote an essay ‘Am I a Snob?’ but the root of her distaste for so many people was always that for a certain sort of sensitive nature any group mentality, working class or other constituted a stifling moral majority fatal to her work and thought.

What I reacted to when I first read Woolf all those years back was her commitment to the poetic feel of everyday. Her writing was about sensitivity itself, the ‘shower of atoms,’ the feel of minute by minute consciousness outside the usual narrative themes of life, erotic desire ending in coupledom, motherhood and so on. Not that this always works when she walks the tightrope between poetry and prose. ‘To the Lighthouse’ is one of the most beautiful and saddest books I’ve ever read for the pain of loss and time going by after the death of the mother Mrs Ramsay. But when I picked up ‘The Waves’ in the library recently I didn’t get that far into it. Maybe I should try again. It seems that when I read I do need what Raymond Carver calls somewhere the ‘feel’ of autobiography. Whereas ‘the Waves’ is beautiful but bodiless. Still it occurs to me that not many of today’s greats like Toni Morrison, AL Kennedy, Zadie Smith do justice to Woolf’s almost asexual, but passionate mental texture of woman’s experience without being sucked into the swirl of erotic relationships. Maybe that’s because they’re prose artists - you have to look to poetry for a similar intensity.

What I reacted to when I first read Woolf all those years back was her commitment to the poetic feel of everyday. Her writing was about sensitivity itself, the ‘shower of atoms,’ the feel of minute by minute consciousness outside the usual narrative themes of life, erotic desire ending in coupledom, motherhood and so on. Not that this always works when she walks the tightrope between poetry and prose. ‘To the Lighthouse’ is one of the most beautiful and saddest books I’ve ever read for the pain of loss and time going by after the death of the mother Mrs Ramsay. But when I picked up ‘The Waves’ in the library recently I didn’t get that far into it. Maybe I should try again. It seems that when I read I do need what Raymond Carver calls somewhere the ‘feel’ of autobiography. Whereas ‘the Waves’ is beautiful but bodiless. Still it occurs to me that not many of today’s greats like Toni Morrison, AL Kennedy, Zadie Smith do justice to Woolf’s almost asexual, but passionate mental texture of woman’s experience without being sucked into the swirl of erotic relationships. Maybe that’s because they’re prose artists - you have to look to poetry for a similar intensity.

‘A Room of One’s Own’

During the end of year holidays in January we switched round furniture and beds in our three and a half room appartment. We have high ceilings which give an illusion of space but only 84m of floorspace. How to accommodate everyone’s various needs in their own private space; starting with our daughters, one ado needs a place where no-one can come in, her little sister a big table to spread out the collection of miniature dolls or ‘pollies’ she talks to for hours on end, their father relaxes by reading online newspapers or listening to hours of Persian music online; their mother wants an uninterrupted space to daydream – not to mention work at writing. After a week of thinking over various configurations of furniture and what-will-happen-when-we-have-houseguests (which happens fairly often since we host family from abroad) /sleepovers (a vital necessity in an ado’s social calender) we managed to create; a duplex for the elder daughter in half a backroom, a study for me behind closed double doors that separate off the bookshelf corner in the living room, a computer corner/ futon flop down area behind by wooden Indian screens - for listening to music and doing nothing in the second biggest room which will also function as a guest room. So far everyone is happy, gets to listen to the sort of music they like without BEING INTERRUPTED, and in my case even start writing posts to ‘Dalloway’s Daughters’.

Circumstances seem to collude in pointing to the obvious place to start for this blog is by talking about ‘A Room of One’s Own’ the essay which Woolf wrote in 1929 for a talk addressed to undergraduates on the opening of the first women’s colleges of Newnham and Girton at Cambridge. I unearthed my copy of this essay - the same yellowing edition I had read years ago as a student and sat up reading it one night after everyone had gone to sleep.

Circumstances seem to collude in pointing to the obvious place to start for this blog is by talking about ‘A Room of One’s Own’ the essay which Woolf wrote in 1929 for a talk addressed to undergraduates on the opening of the first women’s colleges of Newnham and Girton at Cambridge. I unearthed my copy of this essay - the same yellowing edition I had read years ago as a student and sat up reading it one night after everyone had gone to sleep.

feminism and – or – the ‘creative mind’

I think Woolf might been the first woman to get herself labelled feminist by writing explicitly about the connection between women’s lives and writing. And yet her feminism was a fight against this sort of labelling, this relegating of a human being to one specificity merely because as a woman she claimed the right to express that feminine trait of her being.

“anything written with conscious bias is doomed to death.(..)Some collaboration has to take place in the mind between the woman and the man before the art of creation can be accomplished.”

Does she really mean a sort of drawing-room gender bending? The fantastical biography Orlando bears out this ideal of living - aristocratically - beyond sexual difference with Orlando going from being a young man in Queen Elizabeth's court in love with a Muscovite princess; to life as Lady Orlando, encountering the eighteenth century writers Pope, Addison, and Swift and finally experiencing childbirth.

In a ‘A Room of One’s Own’ people always remember the sketch of ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ - the bard’s girl-twin whom Woolf imagines ended up buried at a London crossroads because there is no way that in sixteenth century England a middle-class woman of Shakespeare’s gifts would get an education, or escape early marriage to run away to London and make her way in the theatre as Shakespeare did, without being destroyed by sexual abuse. What is less well-known is this essay is also a discussion on what it is that makes the ‘creative mind’ ‘incandescent’ capable of 'bringing forth' as she says ‘without impediment.’ Looking out her window as she writes at the end of the essay, Woolf sees a man and woman walk down a street towards each other, get into a London taxi together and drive off. She reflects on the ‘happy ending’ effect of those physical opposites, male and female coming together, ‘one has a profound if irrational instinct in favour of the theory that the union of man and woman makes for the greatest satisfaction; the most complete happiness.’ This is interesting – maybe it’s what’s behind that gut reflex with which most women these days in groups in seminars or around dinner tables for instance, (with or without, the presence of men), refuse to identify themselves as feminists. Perhaps it’s merely an instinctive refusal of separatism within the sexes. Again maybe this reflex is connected to time and place. I remember in my first months in France one of my bosses in a language school where I once taught in Paris (English, gorgeous, bilingual and a quietly self-avowed feminist – well she did give up researching a phd on Simone de Beauvoir to earn her living and cast off man after man) - explaining to me that for French women ‘le regard masculin’ is extremely important. Sexual freedom in the public arena - compared for instance to what they call “le puritanisme anglo-saxon” goes with this pressure to be judged on sexual attractiveness, to constantly measure one’s value in aesthetic terms.

Compare this attitude to Iranian women who apply face make-up as we haven’t in this part of Europe since the early seventies - it’s a statement of course of the right to do what they feel like. They refer to themselves as feminists – at least the one I know best does, who happens to be my sister-in-law – without any defensiveness at all. With a big ironic grin which means you’d be naîve not to develop some feminist ruse to laugh off what a woman has to put up with every day under a regime where one woman is officially worth two men.

“anything written with conscious bias is doomed to death.(..)Some collaboration has to take place in the mind between the woman and the man before the art of creation can be accomplished.”

Does she really mean a sort of drawing-room gender bending? The fantastical biography Orlando bears out this ideal of living - aristocratically - beyond sexual difference with Orlando going from being a young man in Queen Elizabeth's court in love with a Muscovite princess; to life as Lady Orlando, encountering the eighteenth century writers Pope, Addison, and Swift and finally experiencing childbirth.

In a ‘A Room of One’s Own’ people always remember the sketch of ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ - the bard’s girl-twin whom Woolf imagines ended up buried at a London crossroads because there is no way that in sixteenth century England a middle-class woman of Shakespeare’s gifts would get an education, or escape early marriage to run away to London and make her way in the theatre as Shakespeare did, without being destroyed by sexual abuse. What is less well-known is this essay is also a discussion on what it is that makes the ‘creative mind’ ‘incandescent’ capable of 'bringing forth' as she says ‘without impediment.’ Looking out her window as she writes at the end of the essay, Woolf sees a man and woman walk down a street towards each other, get into a London taxi together and drive off. She reflects on the ‘happy ending’ effect of those physical opposites, male and female coming together, ‘one has a profound if irrational instinct in favour of the theory that the union of man and woman makes for the greatest satisfaction; the most complete happiness.’ This is interesting – maybe it’s what’s behind that gut reflex with which most women these days in groups in seminars or around dinner tables for instance, (with or without, the presence of men), refuse to identify themselves as feminists. Perhaps it’s merely an instinctive refusal of separatism within the sexes. Again maybe this reflex is connected to time and place. I remember in my first months in France one of my bosses in a language school where I once taught in Paris (English, gorgeous, bilingual and a quietly self-avowed feminist – well she did give up researching a phd on Simone de Beauvoir to earn her living and cast off man after man) - explaining to me that for French women ‘le regard masculin’ is extremely important. Sexual freedom in the public arena - compared for instance to what they call “le puritanisme anglo-saxon” goes with this pressure to be judged on sexual attractiveness, to constantly measure one’s value in aesthetic terms.

Compare this attitude to Iranian women who apply face make-up as we haven’t in this part of Europe since the early seventies - it’s a statement of course of the right to do what they feel like. They refer to themselves as feminists – at least the one I know best does, who happens to be my sister-in-law – without any defensiveness at all. With a big ironic grin which means you’d be naîve not to develop some feminist ruse to laugh off what a woman has to put up with every day under a regime where one woman is officially worth two men.

"dumping emotions"

To go back to “A Room of One’s Own” - any social or psychological condition, says Woolf, that blunts the creative mind is an impediment to creation. She concludes, quoting Coleridge, that the greatest minds are androgynous -‘ a mind that is purely masculine cannot create any more than a mind that is purely feminine’ and it isn’t a mind that takes up the cause of women or devotes its time to their interpretation.’ ‘Perhaps an androgynous mind is less apt to make these distinctions than the single-sexed mind.’ She points out writers she doesn’t like - such as Galsworthy who have ‘not a spark of the woman in them’ and so no ‘suggestive power.’ She’s funny on Proust who has a “little too much of the woman. But that failing is too rare for one to complain of it.”

I think she’s right on creative androgyny. The very masculine world of Raymond Carver for instance incorporates a physical, maternal tenderness for his characters, (if it isn’t outdated to equate tenderness and maternity). Today women writers create real male characters from the inside compare the men in Toni Morrison’s ‘Song of Solomon’ to Charlotte Brontés Mr Rochester or Darcy in ‘Pride and Prejudice.’

Where I part company with Woolf is in her irritation with what she call “sex-consciousness” that she sees as closeting each sex in anger or for men the constant need to assert their superiority out of fear. How can she rail as she does against “the suffrage movement” which she says has a lot to answer for? Or go as far as to say that Shakespeare wouldn’t have written like he did if there had been women suffragettes around in the sixteenth century....Should we blame her for these blind spots? What about that comment that she hoped that women in the future would get beyond making their books ‘a dumping ground for their emotions.’ An odd, guilt-making, (self-disliking?) comment from a pre-modern feminist thinker and precursor of woman’s writing. “And don’t women just have emotions to dump,” snapped a screen-writer friend acerbically when I quoted her this comment – she had just heard on the radio that only fifteen years ago women were allowed into the Viennese Philharmonic Orchestra and that ‘even then the event had caused an uproar.’

“A Room of One’s Own” came out in 1929. Basically, like Freud, Woolf was a creature of her time, despite all that sensitive genius. Isn’t blaming her like taking nineteenth century doctors to task for letting so many women die of puerpural fever in childbirth because they hadn’t a clue about bacterial infection? I suppose there’s a case to be argued here, though personally I’ve never believed that awareness of human equality could be excused on the grounds of lack-of-education. In other words, ignorance, or any other extenuating circumstances. The truth is there in the heart, that woman or man could be me. Most likely Woolf like all of us was afraid of what she couldn’t imagine herself coping with – that rough red housemaid’s complexion from getting up every day at five thirty to clean grates and get the household fires going to provide everyone else’s hot water. Or the desperate anger of a woman trapped without any legal rights at all - in a loveless, seemly, bourgeois marriage – a woman for whom chaining herself to a public railing to win the right to vote would be an emblem of release. Woolf was certainly not as free to act and speak out as we are today - if we use that freedom - but the ‘alternative’ freethinking, freeloving milieu of the Bloomsbury set certainly gave her the space to think and express herself as she wished.

I think she’s right on creative androgyny. The very masculine world of Raymond Carver for instance incorporates a physical, maternal tenderness for his characters, (if it isn’t outdated to equate tenderness and maternity). Today women writers create real male characters from the inside compare the men in Toni Morrison’s ‘Song of Solomon’ to Charlotte Brontés Mr Rochester or Darcy in ‘Pride and Prejudice.’

Where I part company with Woolf is in her irritation with what she call “sex-consciousness” that she sees as closeting each sex in anger or for men the constant need to assert their superiority out of fear. How can she rail as she does against “the suffrage movement” which she says has a lot to answer for? Or go as far as to say that Shakespeare wouldn’t have written like he did if there had been women suffragettes around in the sixteenth century....Should we blame her for these blind spots? What about that comment that she hoped that women in the future would get beyond making their books ‘a dumping ground for their emotions.’ An odd, guilt-making, (self-disliking?) comment from a pre-modern feminist thinker and precursor of woman’s writing. “And don’t women just have emotions to dump,” snapped a screen-writer friend acerbically when I quoted her this comment – she had just heard on the radio that only fifteen years ago women were allowed into the Viennese Philharmonic Orchestra and that ‘even then the event had caused an uproar.’

“A Room of One’s Own” came out in 1929. Basically, like Freud, Woolf was a creature of her time, despite all that sensitive genius. Isn’t blaming her like taking nineteenth century doctors to task for letting so many women die of puerpural fever in childbirth because they hadn’t a clue about bacterial infection? I suppose there’s a case to be argued here, though personally I’ve never believed that awareness of human equality could be excused on the grounds of lack-of-education. In other words, ignorance, or any other extenuating circumstances. The truth is there in the heart, that woman or man could be me. Most likely Woolf like all of us was afraid of what she couldn’t imagine herself coping with – that rough red housemaid’s complexion from getting up every day at five thirty to clean grates and get the household fires going to provide everyone else’s hot water. Or the desperate anger of a woman trapped without any legal rights at all - in a loveless, seemly, bourgeois marriage – a woman for whom chaining herself to a public railing to win the right to vote would be an emblem of release. Woolf was certainly not as free to act and speak out as we are today - if we use that freedom - but the ‘alternative’ freethinking, freeloving milieu of the Bloomsbury set certainly gave her the space to think and express herself as she wished.

writing women

But let’s end on reasons for reading ‘A Room of One’s Own.’ Even today nearly a hundred years later she sounds sharp on the psychology of the sexes. I guess they spent a lot of time talking about that over their cigarette-holders in the drawing rooms of Bloomsbury (and congratulating themselve on being trailblazers. Though she does complain that even one of the nicest, most enlightened men from her bohemian circles can’t take it when he reads a line in a Rebecca West novel referring to men as snobs - he blurts out - “ arrant feminist!”

“Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses” I think this would sound very out of date to my daughters! Clearly what she says about power -sharing in relationships is nolonger just about men and women today but any combination of personalities in which one accepts to reflect the other, trapping both in this “the looking glass vision..that charges the vitality..(...). stimulates the nervous system”

Nevertheless the best reason to read ‘A Room of One’s Own’ is to hear Woolf on the writing process. Not many women writers today talk about writing this way, so prosaically in relation to the everyday routine of life. I love what she says about adapting yourself to interruptions...‘for interruptions there will always be..’ - and this is speaking as a childless woman, though one who openly regretted that fact all her life. Her strange childlessness that the feminist commentators have always noted as a wound inflicted by doctors who decreed that she was not mentally stable enough to bear pregnancy and childbirth. You wonder why she didn't just get pregnant anyway if that was what she longed to do - instead of listening to the professionals whose patriarchal attitude she decried so consistently in her writing. It's worth remembering her comments feel sharp and dry as they often do, she was living on another planet in terms of how people reacted and perceived each other’s rights as human beings. Not only women - any reading of male biographies of the time that include a description of the public school system as for example in Roald Dahl’s ‘Boy’ is a shocking revelation of the sadistic hierarchy taken for granted. So Woolf was working light years ahead of her time when she referred to a book as a psycho-somatic entity and said that one written by a woman has somehow to ‘adapt to the body’ by which she means it (book not body) should be thinner, more concentrated since women with their everlasting multi-tasking tend to work in fits and starts. Women writers must find and accept for themselves “the alternations of work and rest they need, interpreting rest not as nothing doing but as doing something but something that is different and what should that difference be?” All very wise and gentle and applicable today caught up as we are in an endless valorising of productivity. We mustn’t keep comparing she says too. All this constant measuring up of yourself blocks creativity,

“all this pitting of sex against sex and quality against quality; all is claiming of superiority and imputing of inferiority belong to the private school stage of human existence where there are ‘sides’ and it’s important for one side to beat another.”

When she talks about Jane Austen she's thought-provoking too for anyone writing or painting or struggling with any creative project today. Everyone knows Austen’s own self-effacing reference to her ‘art of miniature’ her ‘two inches of ivory’ about her writing - as her nephew says in his memoir, ‘in the general sitting room subject to all kinds of casual interruptions,’ how she was glad that a hinge creaked so that she covered up what she was doing with blotting paper. Would she have written better novels, wonders Woolf, if she hadn’t been so intent on covering up what she was doing? She looks into ‘Pride and Prejudice’ to see if she can fault its narrowness but can’t find anything,

“That perhaps was the chief miracle about it. Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. This was how Shakespeare wrote, .(..) the minds of both had consumed all impediments...(...)for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word she wrote and so does Shakespeare. If Jane Austen suffered in any way from her circumstances it was in the narrowness of life that was imposed upon her. It was impossible for a woman to go about alone. ...But perhaps it was the nature of Jane Austen not to want what she had not. Her gift and her circumstances matched each other perfectly.”

Hmm. Woolf has an almost Buddhist approach to the toxicity of anger in conflict. My first reaction was to dismiss this attitude as very British stiff upper lip approach, that victorian drawing room training that all the great twentieth century revolutions broke with by revindicating first and foremost the right to be angry. However, when you argue angrily says Woolf, like men are angry with women, the listener hears not so much the argument as the personal reaction of anger and then responds in kind.

Turning this over in my mind I thought about a middle-aged Iranian dissident I know from contact with the disaspora here, who has spent his life in and out of prison. A writer and historian who continues to produce texts despite nearly losing his eyesight and suffering so much from broken health. This man and some women dissidents too whom I’ve met, behave with an immutable, stolid attitude of resistance. No satire, or vindictive railing, less hatred than enormous confidence and patience. A philosophic approach to the enemy, understanding his defects of education, by which Woolf meant their being raised to go to war when need be, or to make money and more money “when it is a fact that five hundred pounds a year will keep one alive in the sunshine.”

I guess that’s the trick, the more you understand, the more easily you cast off the need for anger, fear and bitterness.

But by far the best moment of all from ‘A Room of One’s Own’ comes at the end where she’s standing in front of a shelf of woman writers - the selection goes from Aphra Benn to the jewel in the crown – Jane Austen - then the Brontés and the other Victorians who had to take mens’ names to get published...and that’s all. She has no idea you think gleefully, of all the wealth that lay ahead, the endless opening out and kicking aside of restraints. Just the most rapid glance up at my bookshelf takes in a huge explosion in the mind, in English alone ; E. Annie Proulx, Jeanette Winterson, Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Carol Ann Duffy, Doris Lessing, Sylvia Plath, Jane Gardam, Anita Desai, Monica Ali...and on and on.

What luck to be alive now, in what she calls ‘the twilight of the future’.

“Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses” I think this would sound very out of date to my daughters! Clearly what she says about power -sharing in relationships is nolonger just about men and women today but any combination of personalities in which one accepts to reflect the other, trapping both in this “the looking glass vision..that charges the vitality..(...). stimulates the nervous system”

Nevertheless the best reason to read ‘A Room of One’s Own’ is to hear Woolf on the writing process. Not many women writers today talk about writing this way, so prosaically in relation to the everyday routine of life. I love what she says about adapting yourself to interruptions...‘for interruptions there will always be..’ - and this is speaking as a childless woman, though one who openly regretted that fact all her life. Her strange childlessness that the feminist commentators have always noted as a wound inflicted by doctors who decreed that she was not mentally stable enough to bear pregnancy and childbirth. You wonder why she didn't just get pregnant anyway if that was what she longed to do - instead of listening to the professionals whose patriarchal attitude she decried so consistently in her writing. It's worth remembering her comments feel sharp and dry as they often do, she was living on another planet in terms of how people reacted and perceived each other’s rights as human beings. Not only women - any reading of male biographies of the time that include a description of the public school system as for example in Roald Dahl’s ‘Boy’ is a shocking revelation of the sadistic hierarchy taken for granted. So Woolf was working light years ahead of her time when she referred to a book as a psycho-somatic entity and said that one written by a woman has somehow to ‘adapt to the body’ by which she means it (book not body) should be thinner, more concentrated since women with their everlasting multi-tasking tend to work in fits and starts. Women writers must find and accept for themselves “the alternations of work and rest they need, interpreting rest not as nothing doing but as doing something but something that is different and what should that difference be?” All very wise and gentle and applicable today caught up as we are in an endless valorising of productivity. We mustn’t keep comparing she says too. All this constant measuring up of yourself blocks creativity,

“all this pitting of sex against sex and quality against quality; all is claiming of superiority and imputing of inferiority belong to the private school stage of human existence where there are ‘sides’ and it’s important for one side to beat another.”

When she talks about Jane Austen she's thought-provoking too for anyone writing or painting or struggling with any creative project today. Everyone knows Austen’s own self-effacing reference to her ‘art of miniature’ her ‘two inches of ivory’ about her writing - as her nephew says in his memoir, ‘in the general sitting room subject to all kinds of casual interruptions,’ how she was glad that a hinge creaked so that she covered up what she was doing with blotting paper. Would she have written better novels, wonders Woolf, if she hadn’t been so intent on covering up what she was doing? She looks into ‘Pride and Prejudice’ to see if she can fault its narrowness but can’t find anything,

“That perhaps was the chief miracle about it. Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. This was how Shakespeare wrote, .(..) the minds of both had consumed all impediments...(...)for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word she wrote and so does Shakespeare. If Jane Austen suffered in any way from her circumstances it was in the narrowness of life that was imposed upon her. It was impossible for a woman to go about alone. ...But perhaps it was the nature of Jane Austen not to want what she had not. Her gift and her circumstances matched each other perfectly.”

Hmm. Woolf has an almost Buddhist approach to the toxicity of anger in conflict. My first reaction was to dismiss this attitude as very British stiff upper lip approach, that victorian drawing room training that all the great twentieth century revolutions broke with by revindicating first and foremost the right to be angry. However, when you argue angrily says Woolf, like men are angry with women, the listener hears not so much the argument as the personal reaction of anger and then responds in kind.

Turning this over in my mind I thought about a middle-aged Iranian dissident I know from contact with the disaspora here, who has spent his life in and out of prison. A writer and historian who continues to produce texts despite nearly losing his eyesight and suffering so much from broken health. This man and some women dissidents too whom I’ve met, behave with an immutable, stolid attitude of resistance. No satire, or vindictive railing, less hatred than enormous confidence and patience. A philosophic approach to the enemy, understanding his defects of education, by which Woolf meant their being raised to go to war when need be, or to make money and more money “when it is a fact that five hundred pounds a year will keep one alive in the sunshine.”

I guess that’s the trick, the more you understand, the more easily you cast off the need for anger, fear and bitterness.

But by far the best moment of all from ‘A Room of One’s Own’ comes at the end where she’s standing in front of a shelf of woman writers - the selection goes from Aphra Benn to the jewel in the crown – Jane Austen - then the Brontés and the other Victorians who had to take mens’ names to get published...and that’s all. She has no idea you think gleefully, of all the wealth that lay ahead, the endless opening out and kicking aside of restraints. Just the most rapid glance up at my bookshelf takes in a huge explosion in the mind, in English alone ; E. Annie Proulx, Jeanette Winterson, Nadine Gordimer, Toni Morrison, Carol Ann Duffy, Doris Lessing, Sylvia Plath, Jane Gardam, Anita Desai, Monica Ali...and on and on.

What luck to be alive now, in what she calls ‘the twilight of the future’.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)